A chat with renowned chef, author, televison host and artist Jacques Pépin

Celebrated French-American chef Jacques Pépin was born in 1935 and developed his passion for cooking as a child while helping out in his parents’ restaurant. His distinguished career started at the age of 13 when he apprenticed at Grand Hôtel de L’Europe in his native Bourg-en-Bresse. Pépin lived in Paris for almost eight years in the 1950s, not only working at Hôtel Plaza Athénée, but also cooking for three heads of state, including Charles de Gaulle.

After moving to New York in 1959, he worked at renowned restaurant Le Pavillion and later became director of research and development for Howard Johnson’s. Together with close friend Juia Child, Pépin taught Americans how to cook through the acclaimed public television series, Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home.

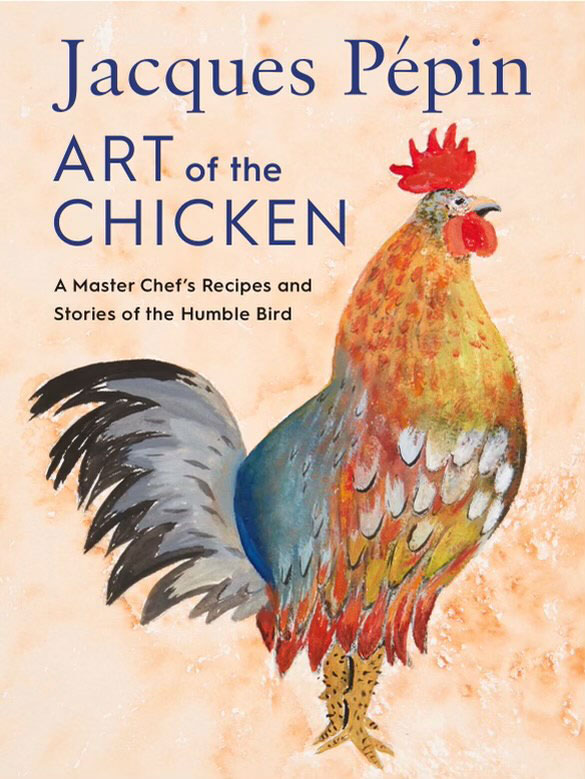

Jacques Pépin lives in Connecticut and has been painting for more than half a century. His 31st book, Art of the Chicken: A Master Chef’s Stories and Recipes of the Humble Bird, will combine stories and drawings of chickens with chicken and egg recipes. It is due out this fall.

Earlier this year, I had the great honor of interviewing Jacques about his exceptional career and time in France.

What is your fondest food memory of your childhood in France?

Those early years were during the war when food was very scarce. That’s probably why I’m pretty miserly in the kitchen. My mother used absolutely everything she could get her hands on and would bike to farms to get a couple of eggs or whatever was available.

My family had at least ten restaurants and they were all run by women who were formidable cooks. I was the first man to go into that business. I have many wonderful food memories, from eating the greatest bread and butter to my mother’s chicken in cream sauce or my aunt’s pike quenelles. While growing up, all special occasions revolved around food, and that has remained the same to this day.

What did you enjoy most about your time in Paris?

Well, it was the first time I was exposed to classic French cooking, and we had to conform to the way things were done back then. For example, at the Plaza Athénée, there were 48 chefs in the kitchen and they all made the lobster soufflé exactly the same way. It wasn’t like now, where it’s all about the chef’s creativity.

They were very generous at the Plaza Athénée. We had a soccer team to play on as well as access to a little canoe on the Seine and a private library. I started doing a great deal of reading and it changed my life.

When I worked the night shift and was done at 2:30 a.m., we would visit places like Les Halles. I also enjoyed going to the Opéra-Comique. Back then, it was funded by the government and going there cost about as much as putting a coin in a jukebox! It was engrossing and I continued going there for years. I was 17, developed cultural interests and discovered a whole new world. The 50s in Paris were extraordinary.

You obtained a Master’s degree in 18th-century French literature at Columbia University.

When I left for the United States in September of 1959, it was my intention to only stay a few years, study the language and then return to France. I came here on a student boat (Ascania) and during the trip, I asked a professor from New York State about the best school. He recommended Columbia, which I’d never heard of. I arrived in New York on the 12th and by the end of the month, I was enrolled in Columbia’s English for Foreign Students program. I continued studying, eventually getting my B.A. and then an M.A. in 1972.

It’s funny because I had originally suggested writing my Ph.D. thesis on French food history in the context of French literature. They dismissed the idea, but I later took it to Boston University. Before that, food was at the bottom of the social scale. No mother would have wanted her daughter to marry a chef. Now a chef is considered a genius!

(Together with Julia Child and director Rebecca Alssid, Pépin launched a master’s program in gastronomy and a certificate program in culinary arts at Boston University. He has taught the culinary arts program since 1992.)

What did you miss most about France when you moved to New York?

I didn’t really miss much and was actually very excited to be in a new country. The day after I had arrived, I was taken to Le Pavillon to meet executive chef Pierre Franey. I was expecting a very formal experience. In France, you are immediately asked for all your certificates. I had them all ready, but Pierre wasn’t interested. I didn’t have to call him ‘monsieur’ either. I immediately discovered the democratic side of America, much less formal than in France at the time. That was probably one of the reasons I stayed here.

Which French traditions have you maintained?

There is a large pétanque club here. We play the entire summer and organize big dinners with a lot of wine. Another tradition I’ve brought back from France is foraging for mushrooms. It reminds me of when I was a child and did the same with my brothers and father. Since we live close to the shore, I catch whitebait with a net every summer. I also have a garden where I grow herbs and vegetables. My life, without any question, revolves around food in many ways, and these are the traditions I’ve passed on to my daughter Claudine and my grand-daughter.

You were introduced to colleague and great friend Julia Child by Helen McCully (food editor of House Beautiful) in 1960. What do you remember most about your friendship with Julia?

I had been introduced to James Beard, Craig Claiborne (food editor of the New York Times) and Julia Child very soon after I had arrived in New York. Back then they were the trinity of cooking in America. The food world was quite small. All the chefs I knew in New York back then were French, Italian, German, etc. I didn’t know many American chefs.

Julia had sent Helen her manuscript for Mastering the Art of French Cooking, and Helen asked me to read it. When we met, Julia had just come back from France and we actually spoke more French than English. We quickly became great friends. I cooked with her at her house in Boston, and she would visit me as well. We shared many dinners at restaurants, too.

It was great fun when we cooked together for television. We never worked with a recipe or script and only decided what we were going to make the day before. It must’ve been very difficult for the cameraman and producer because they had no idea what we were doing. A 30-minute show would take more than an hour and a half, and Julia would tell them: “We’ll let you know when we’re finished!” We had no time limit, cooked whatever we wanted and shared a bottle of wine. For me it was like cooking with a friend.

Where did you get your inspiration for Art of the Chicken, due out this fall?

Where did you get your inspiration for Art of the Chicken, due out this fall?

When my wife Gloria and I invited guests to our house for dinner, I would illustrate the menus and keep them in a book. I have 12 large books that tell the story of my life and are full of special memories and time spent with my family. My daughter was here recently and asked what she had eaten for her fourth birthday, so we looked it up and found she had drawn a little chicken. I realized I painted a lot of chickens and have about 130 illustrations. I didn’t want to make another book of only recipes. It will be a book of stories about eggs and chickens, similar to The Apprentice (2003). There will be recipes, but I will explain them as I would to a friend. I am very excited about this book, which should be out by September.

So why the fascination with chicken? Is it because you were born in Bourg-en-Bresse, which is famous for its poultry?

So why the fascination with chicken? Is it because you were born in Bourg-en-Bresse, which is famous for its poultry?

(Laughs). I guess so. Our chickens are considered one of the best in France, of course, and they wear the colors of the flag: bleu (feet), blanc (feathers), rouge (comb). But perhaps also because of the ‘coq gaulois’ (Gallic rooster) which is a symbol of France.

You call yourself a glutton. What is your ultimate French meal?

It would be the food of my childhood: frogs’ legs, escargots, chicken in cream sauce and certainly the fromage blanc from Lyon, which is mixed with cream, garlic and chives. The kind of tastes that stay with you for the rest of your life.

You’ve mentioned chicken in cream sauce a few times. Is that a favorite dish?

Yes, it was one of my mother’s favorite ways to make chicken for special occasions. It was considered a luxury dish. If I close my eyes, I can still taste it.

(The recipe for poulet à la crème can be found in The Apprentice.)

So which wine would you serve with it?

Any type of wine, really. (Laughs) Well, I’m from the Beaujolais region, so perhaps a Gamay… but a Sauvignon Blanc is also fine. For me it really doesn’t matter. Whether it’s a Bordeaux, a Burgundy, a Côtes du Rhône, I’ll drink it. Sometimes I’ll pair a wine with a dish, but usually any wine is fine. Wine is very important to me. Every day around four or five in the afternoon, I start with a glass of white wine and continue with some red for dinner.

It’s a lovely way to end the day, isn’t it?

Yes, absolutely!

What is the essence of French cooking?

For me it’s about sharing at the table more than anything else. It starts with the buying of food (from the market or the farmer), the simplicity of the recipes and quality of the ingredients. In a sense, it’s a whole lifestyle.

QUICK FIRE

Apéritif or digestif?

Apéritif.

Olive oil or butter?

Both.

Apple pie or tarte aux pommes?

Tarte aux pommes. I am still not used to all that cinnamon!

With thanks to Jacques Pépin

Photos courtesy of Tom Hopkins and Jacques Pépin